UNESCO has this to say about their origins:

There is relatively little known about the origins of the caravanserai. Etymologically, the word is a compound of the Persian kārvān, meaning caravan or group of travelers, and sara, a palace or enclosed building, with the addition of the Turkish suffix -yi. One of the earliest examples of such a building can be found in the oasis city of Palmyra, in Syria, which developed from the 3rd century BC as a place of refuge for travelers crossing the Syrian desert. Its spectacular ruins still stand as a monument to the intersection of trade routes from Persia, India, China and Roman Empire. As trade routes developed and became more lucrative, caravanserais became more of a necessity, and their construction seems to have intensified across Central Asia from the 10th century onwards, particularly during periods of political and social stability, and continued until as late as the 19th century. This resulted in a network of caravanserais that stretched from China to the Indian subcontinent, Iran, the Caucasus, Turkey, and as far as North Africa, Russia and Eastern Europe, many of which still stand today.

This site has an interesting map of known caravansaries in Turkey.Iranica Online talks about caravansary layout:

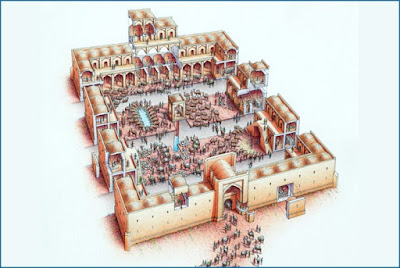

The normal caravansary consisted of a square or rectangular plan centered around a courtyard with only one entrance and arrangements for defense if necessary. Whether fortified or not, it at least provided security against beasts of prey and attacks by brigands. This architectural type developed in the 1st millennium b.c. in Urartian and Mesopotamian architecture (Kleiss, 1979; Frankfort, pp. 73ff.) and was further evolved in the ancient world, in the palace architecture of the ancient Greeks, for example, the palace of Demetrias called the Anaktoron, with rooms opening from a large colonnaded courtyard (Marzolff; pp. 42ff.); Greek and Roman peristyle houses; and a.d. 3rd- and 4th-century Roman castles like Burgsalach (Ulbert and Fischer, p. 87, fig. 67) and the Palast-Burg in Pfalzel, near Trier (Cüppers, pp. 163ff.). The same building type persisted in the Near East in structures like the church-house from Dura Europos (a.d. 3rd century; Klengel, p. 162). It achieved its fullest expression, however, in the work of Muslim architects: in the desert palaces of the Omayyads, hypostyle (or “Arab”) mosques, Koran schools (madrasas), and above all rebāṭs and caravansaries. It thus played an integral part in the architectural history of the Islamic lands. The Crusaders brought it to Europe, where it was combined with the cruciform aisles of Christian architecture and adopted for the castles of the Teutonic Knights (Holst), as well as for Renaissance (e.g., the castle of Aschaffenburg; Wasmuths Lexikon, p. 191) and Baroque palaces (Wasmuths Lexikon, pp. 321ff.); it survived in modern architecture in buildings for special purposes, like 19th-century museums (e.g., the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin).

Take a moment today and check out some of these links, and learn a little about caravansaries, and imagine all the stories over all those years, that must have unfolded therein.

Check out Beneath a Brass Sky, too!

Comments

Post a Comment